When Shohei Ohtani signed his landmark $700 million deferred deal with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2023, most baseball fans had only heard of one other deferred contract. That deal, the infamous Bobby Bonilla buyout, has become a part of baseball lore and pop culture alike. Most baseball fans, even the hardcore fans, don’t realize that deferred deals in Major League Baseball go back long before Bonilla. Here is a look at some of the earliest known deferred MLB contracts, the stories behind them, and how these contracts have evolved over the years.

Ted Williams

While there were rumors of other deferred contracts back in his day, Ted Williams was the first one that eventually leaked out into the public domain. Williams’ deal was not about retirement or saving the team money to spend on other players. It was about spite. The Boston Red Sox great signed a $150,000 contract back in the 1950s, but deferred $50,000. Williams purposely reduced his salary for a year in an effort to reduce the money he would lose in his upcoming divorce settlement and alimony payments. The story came out decades later in Ben Bradlee Jr’s book The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams, published in 2013.

Catfish Hunter

Catfish Hunter’s 1974 deal with then Oakland A’s owner (and known cheapskate) Charles O. Finley became famous not for the deferral, but for it not being paid. Hunter signed a $100,000 contract with $50,000 to be paid directly to him and the other $50,000 to be put into an annuity for the star pitcher’s retirement. Finley refused to put the money in the annuity. After a long, drawn-out process, MLB had its first-ever player arbitration hearing, and eventually, its first-ever free agent.

The future Hall of Famer was coming off a Cy Young season and was free to negotiate with every major league team. 22 offers poured in, and Hunter ended up signing 1975’s only multi-year contract. His ground-breaking five-year deal included more deferred retirement money, bonuses, life insurance, and college endowments for his children. It also included a new Buick every year for the length of the contract, and a raft of other benefits. Hunter’s family was set for life, and MLB contracts and labor relations were forever changed.

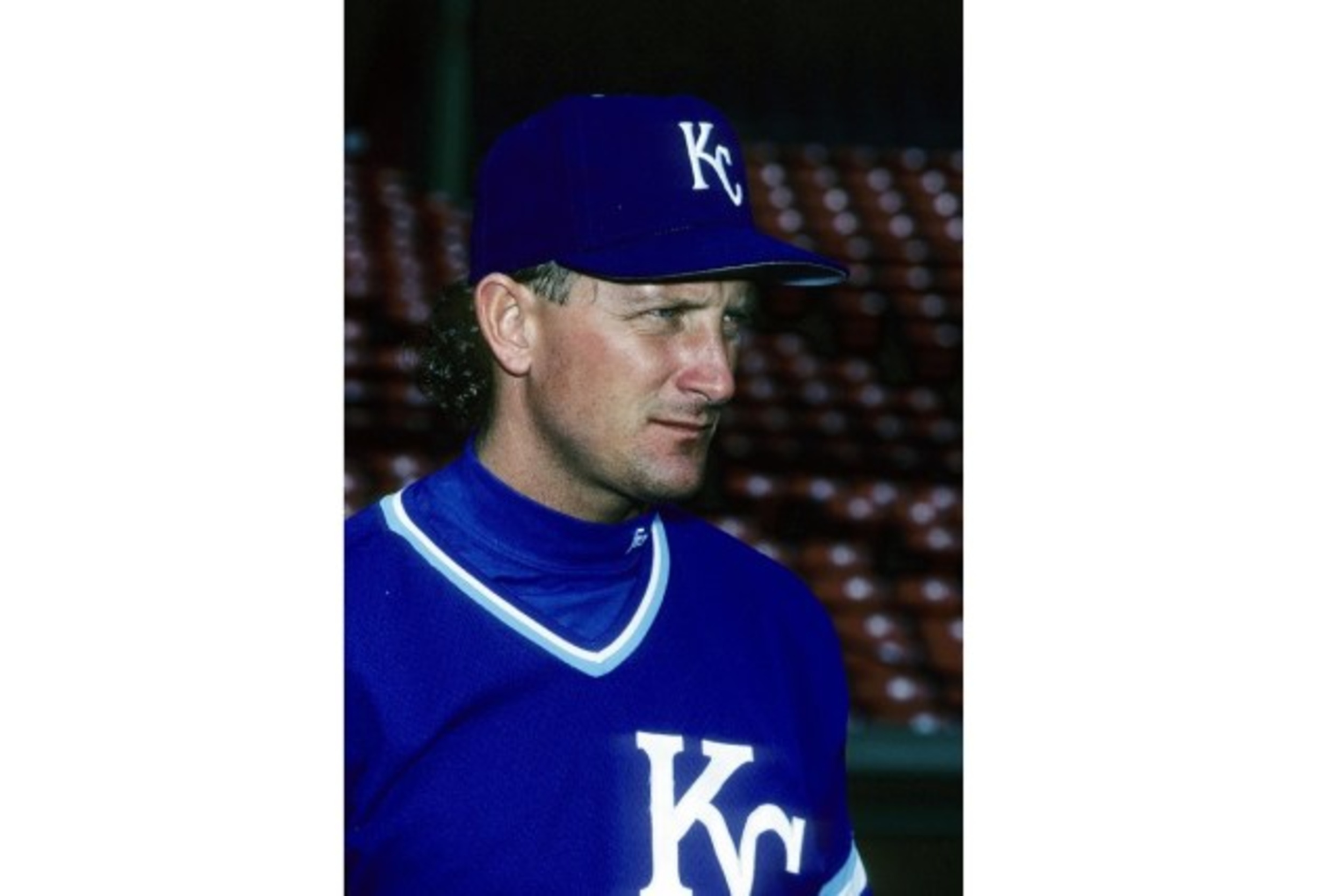

Bret Saberhagen

Everyone remembers Bonilla’s deal with the New York Mets, but not the direct precursor that shaped it. In 1995, Bret Saberhagen signed with the Mets after eight years and two Cy Young awards with the Kansas City Royals. Saberhagen was at his peak, but he wanted to make sure he was set for life after baseball. Part of his deal with New York was a deferment that would pay him $250,000 per year for 25 years, starting in 2004. The deal turned out to be a wise one. The rest of Saberhagen’s career was marred by injuries, and he retired after the 2001 season.

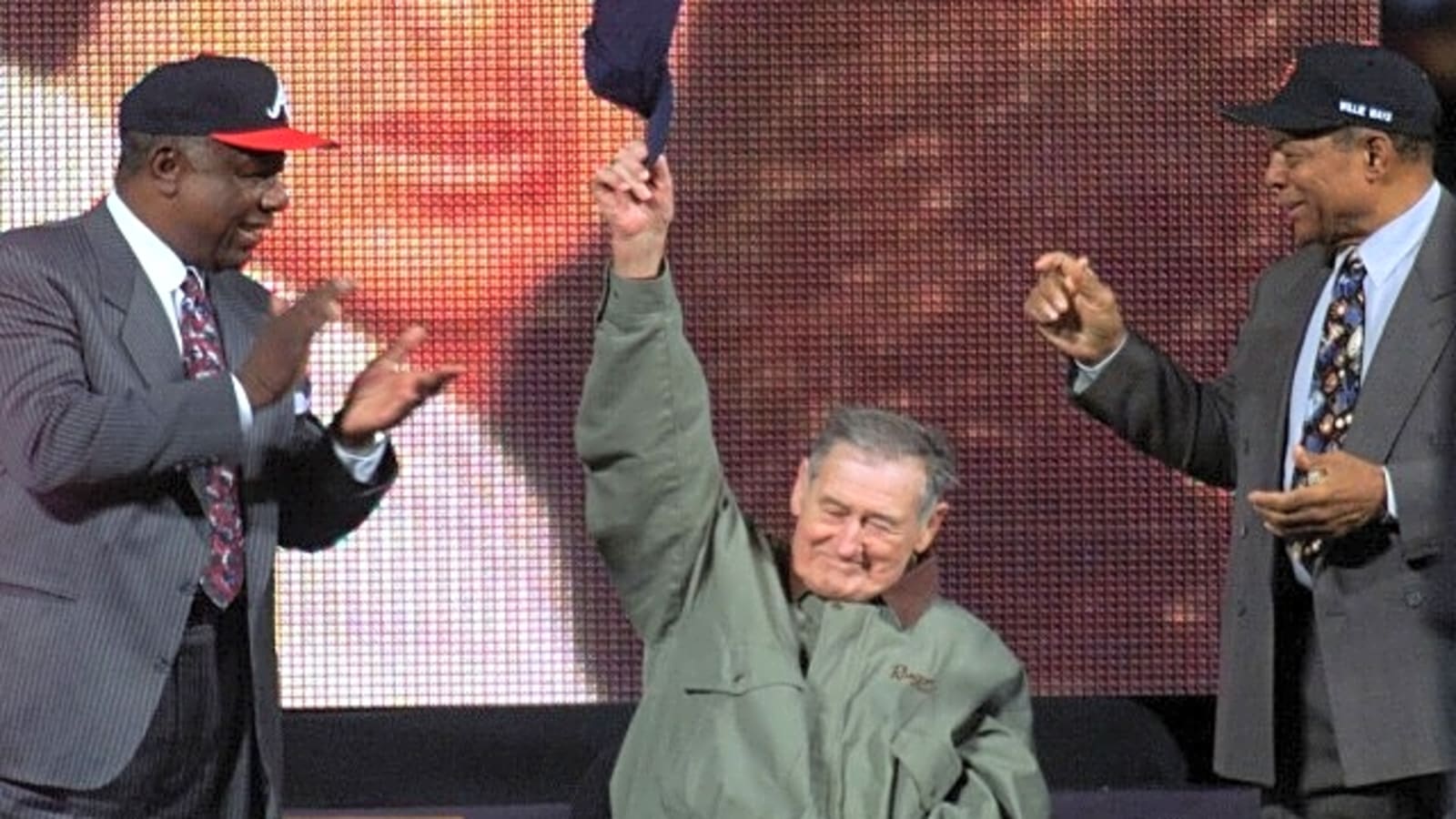

Bobby Bonilla

Bonilla had been at the peak of his career during his first go-round with the Mets. By the time he returned to them again in 1999 in a trade with the Miami Marlins, he was 36 and a shell of his former self. Bonilla had two years left on his deal. In 1999, he played in just 60 games and hit a measly .160 with four home runs. By 2000, New York wanted to buy out the final year and $5.9 million left on Bonilla’s contract. Mets owner, Fred Wilpon, did not want to pay the money up front, though. He instead wanted to sink money into one of Bernie Madoff’s infamous investments…that later turned out to be a Ponzi scheme.

New York cut a deal with the aging third baseman to pay him the money in deferred payments from 2011 to 2035. Based on the interest rate agreed upon, Bonilla receives $1,193,248.20 every July 1. It has become such a part of baseball lore that Mets fans call every July 1 Bobby Bonilla Day. Even current New York owner Steve Cohen embraces the “holiday.”

While the Mets deal is the one that everyone talks about, it is not the first deferral that Bonilla signed up for. His first tenure with New York ended with a trade to the Baltimore Orioles in 1995. His run with the Orioles ended after the following year. Baltimore, however, also chose to defer some of Bonilla’s money. Seeing what the Mets did with Saberhagen, Bonilla set himself up to receive $500,000 per year on July 1 from 2004 through 2028. Saberhagen’s and Bonilla’s 1995 deals influenced the more famous New York “Bobby Bonilla Day” one.

Other Deferred Deals

These deferred deals have become more and more prevalent over the years. Stars like Bruce Sutter, Manny Ramirez, Ken Griffey Jr., Max Scherzer, and Chris Davis all agreed to deferred money. When the Dodgers signed Ohtani’s deal, they did it with multiple future World Series championships in mind. Los Angeles has also deferred money on deals for Mookie Betts, Blake Snell, Freddie Freeman, Will Smith, Teoscar Hernandez, Tanner Scott, and Tommy Edman. In total, the team has deferred over $1.051 billion in salary, much of which is Ohtani’s money.

End Of My Bobby Bonilla Deferred Contract Rant

Many baseball fans cried foul when the Ohtani deal was announced. While it seems like a way to cheat the competitive balance tax, it is smart and totally legal. Any major league team could have done the same thing. A lot of fans hate on the Dodgers for the Ohtani deal, but that hate should be shared equally with their team for not doing the same. Who is to say that their team couldn’t have snagged Ohtani, Juan Soto, or Aaron Judge by making a similar deferred salary pitch?

Most fans don’t understand that the deferred salaries count towards the CBT Tax based on their average annual value. The deferred money counts against the CBT based on its current value, taking into account any future devaluation or inflation. One dollar in the future will be worth significantly less than its present value, especially if there is little or no interest involved. Ohtani’s contract is interest-free, unlike Bonilla’s contracts, which were based on 8% interest. Ohtani is deferring $ 68 million of his $70 million annual salary. His contract counts as $46 million per year against the Dodgers’ CBT number.

It is not necessarily simple math, but it is smart math–smart math that any team can use. I am frankly surprised that more MLB teams have not done this. Ohtani takes $2 million this year. The Dodgers deposit the present value of his $68 million deferment, $46 million, into an escrow account. That escrow grows to be the $68 million he collects in 2035. The same happens next year for 2036. During the deferment years, Ohtani does not count against the CBT because the money is paid into escrow during the years he is under contract. I am no accountant, but that sounds like a pretty good deal for Los Angeles.

While it seemed soul-crushing for many baseball fans to watch the Dodgers buy up free agents the last couple of years, I cannot blame them for doing it. It worked for them. They won the World Series last year, and they have a good shot at doing it again for the next several years. Sorry, New York Yankees fans, they are the new “Evil Empire.” If small market teams like the Pittsburgh Pirates, (formerly Oakland) Athletics, Miami Marlins, and Milwaukee Brewers all utilized this strategy, just think how much better their teams would be.

More must-reads:

- Jerry Jones again proves he shouldn't be making decisions for Cowboys

- Jelena Ostapenko responds to racism allegations after post-match confrontation with Taylor Townsend

- The 'NFL QB season rushing leaders' quiz

Breaking News

Trending News

Customize Your Newsletter

+

+

Get the latest news and rumors, customized to your favorite sports and teams. Emailed daily. Always free!