[Editor’s note: This article is from The Spun’s “Then and Now” magazine, featuring interviews with more than 50 sports stars of yesteryear. Order your copy online today, or pick one up at retail racks and newsstands nationwide.]

Malcolm Smith was in a Los Angeles-area tennis shop last spring when the former NFL linebacker bumped into Cooper Kupp, who caught eight passes for 92 yards and two touchdowns to win Super Bowl MVP honors in the Rams’ 23-20 win over the Cincinnati Bengals on Feb. 13, 2022.

“I was like, ‘Oh, man, Super Bowl MVP,’” Smith said. “I didn’t think he would know who I was, and it took me a second to realize who he was. Then he looked at me, and it was kind of like, ‘Oh, yeah.’”

Kupp and Smith, who was buying a racket for his daughter, were the only customers in the store that day who knew there were two Super Bowl MVPs in the house.

One was immediately recognizable thanks to his signature bushy beard and superstar pedigree, which includes an AP Offensive Player of the Year award and a triple crown title for leading the NFL in catches, reception yards and touchdowns in 2021.

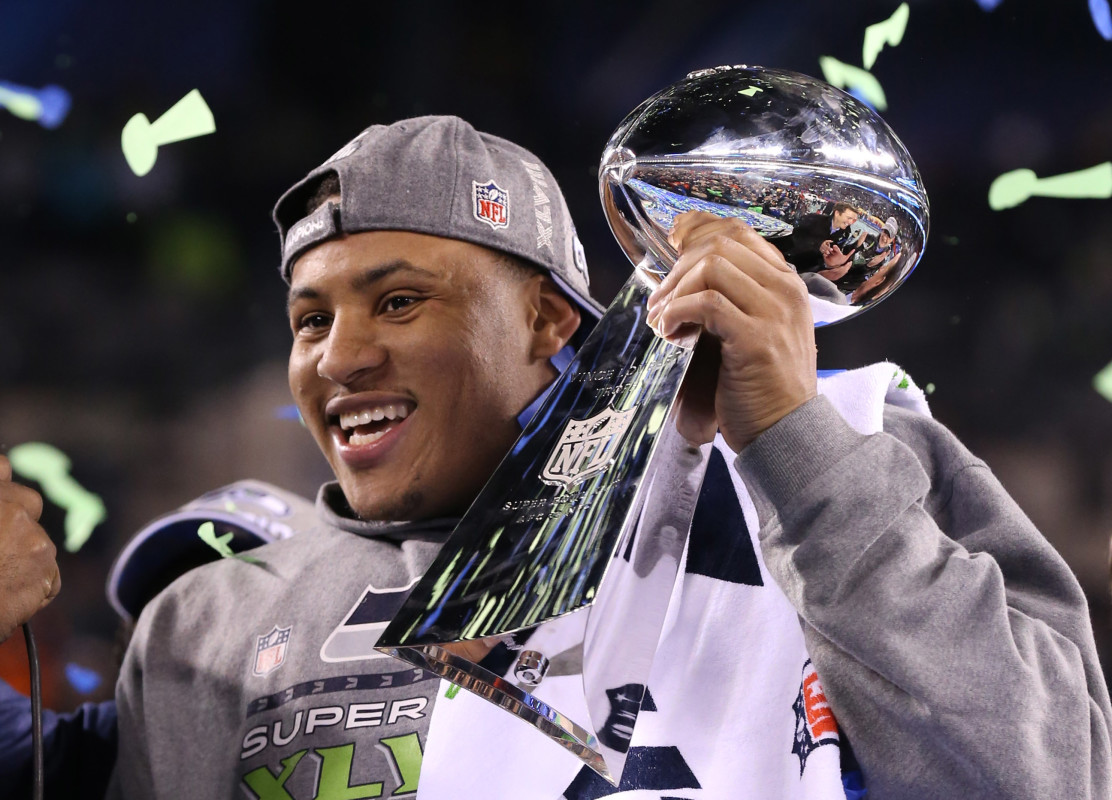

The other was Smith, who returned an interception 69 yards for a touchdown, recovered a fumble and had nine tackles in the Seattle Seahawks’ 43-8 victory over the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl XLVIII after the 2013 season.

For every Tom Brady, Joe Montana or Patrick Mahomes — established stars who have won a combined 10 Super Bowl MVPs — there is an unlikely Super Bowl hero who either hoisted an MVP trophy or made a game-turning play, such as Malcolm Smith, Doug Williams, Mike Jones, David Tyree or Timmy Smith, to help secure an NFL championship.

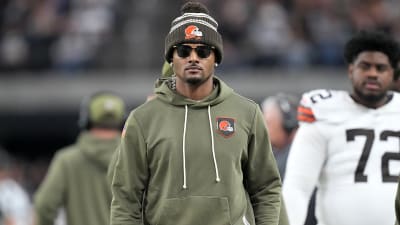

MALCOLM SMITH

What he did: The Denver Broncos were on the 16th play of a second-quarter drive, looking to cut into a 15-0 deficit when quarterback Peyton Manning was hit by Seattle defensive end Cliff Avril, a key cog in the Seahawks’ Legion of Boom defense, as he threw a wobbly pass intended for running back Knowshon Moreno.

Malcolm Smith, the Seahawks linebacker, stepped in front of Moreno, intercepted the deflected ball and raced 69 yards into the end zone for a 22-0 lead, a potential 14-point swing in an eventual blowout win for Seattle.

Smith, however, failed to nail the dismount after his score, his awkward attempt to slam-dunk the ball over the goal post falling well short.

“My hamstrings had been through a lot that season, and that was a pretty long run,” said Smith, now 36. “I slowed down [after reaching the end zone], and then the idea popped into my head, like, ‘Hey, let’s jump.’ I can barely run and dunk in real life, so with pads on, I needed a fast break. But that was too long of a fast break.”

Serving as a reserve for most of his four years in Seattle, Smith parlayed his Super Bowl MVP into a two-year, $7 million deal and a starting job with the Oakland Raiders. He went on to play for four more teams in his 10-year career before retiring from the NFL after 2021.

Where he is now: Smith, who earned an economics degree from USC, returned to school after his football career. He completed an MBA program at Penn’s Wharton School in May 2025.

Married with two daughters, ages 8 and 6, and living in Los Angeles, Smith hopes to be an entrepreneur with an eye toward providing financial guidance to other pro athletes.

“They say family, friends and fools are great people to raise money from, and a lot of times we as athletes fall into the fools category,” Smith said. “So, I wanted to go back to school and help contribute to that changing, whether it’s through education in support of other athletes, mentorship and finding [them] legitimate [investment] opportunities.”

DOUG WILLIAMS

What he did: Doug Williams awoke the day before Super Bowl XXII with a raging toothache. By midday, the Redskins quarterback was in a San Diego dentist’s office undergoing a four-hour root canal.

Pain found Williams again late in the first quarter of the Jan. 31, 1988, game, when he twisted his right knee and limped to the sideline, Washington trailing Denver by 10 points.

“The only thing I was thinking was, ‘If it’s not bad enough, I’m gonna finish this game,’ ” said Williams, now 70.

The injury — later diagnosed as a hyperextended knee — was severe enough for Williams to undergo surgery later that week but not enough to slow him in Washington’s 42-10 win.

Williams, who lost the only two games he started in the 1987 regular season, returned early in the second quarter. He completed 18 of 29 passes for 340 yards and four touchdowns, the four scoring throws coming during a record 35-point second quarter.

Williams was the first Black quarterback to win the Super Bowl and be named MVP. As he walked off the Jack Murphy Stadium field in San Diego, he thought of the circuitous route he took — from Grambling State, the contract dispute that prompted him to leave Tampa Bay for the USFL in 1983 and his bumpy return to the NFL, where he played sparingly behind Redskins starter Jay Schroeder in 1986-87.

“I call it the road less traveled,” Williams said.

Where he is now: Williams is in his second year as adviser to Commanders general manager Adam Peters and 12th season with the organization overall. His road back to Washington sounds like a Johnny Cash song — he’s been everywhere, man.

Williams coached at two Louisiana high schools, including his alma mater, Zachary, whose stadium is named after him. He was a Naval Academy and Morehouse assistant before replacing legendary coach Eddie Robinson at Grambling in 1988.

Williams served in the front offices with the Jacksonville Jaguars, Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Virginia Destroyers (United Football League) before returning to Washington in 2014.

“I enjoyed every minute,” Williams said of his journey, “because at every stop, I met somebody who helped me along the way.”

Now, Williams, a father of eight and grandfather of 11, is paying it forward, serving as a mentor to Commanders star Jayden Daniels, the latest in a long line of Black NFL quarterbacks that Williams helped pave the way for.

“I got to open the minds of the people making the decisions, the coaches, GMs and owners,” said Williams. “It became less of a ‘Black-and-white’ thing and more of a ‘who-can-help-us-win’ thing. I take a lot of pride in that.”

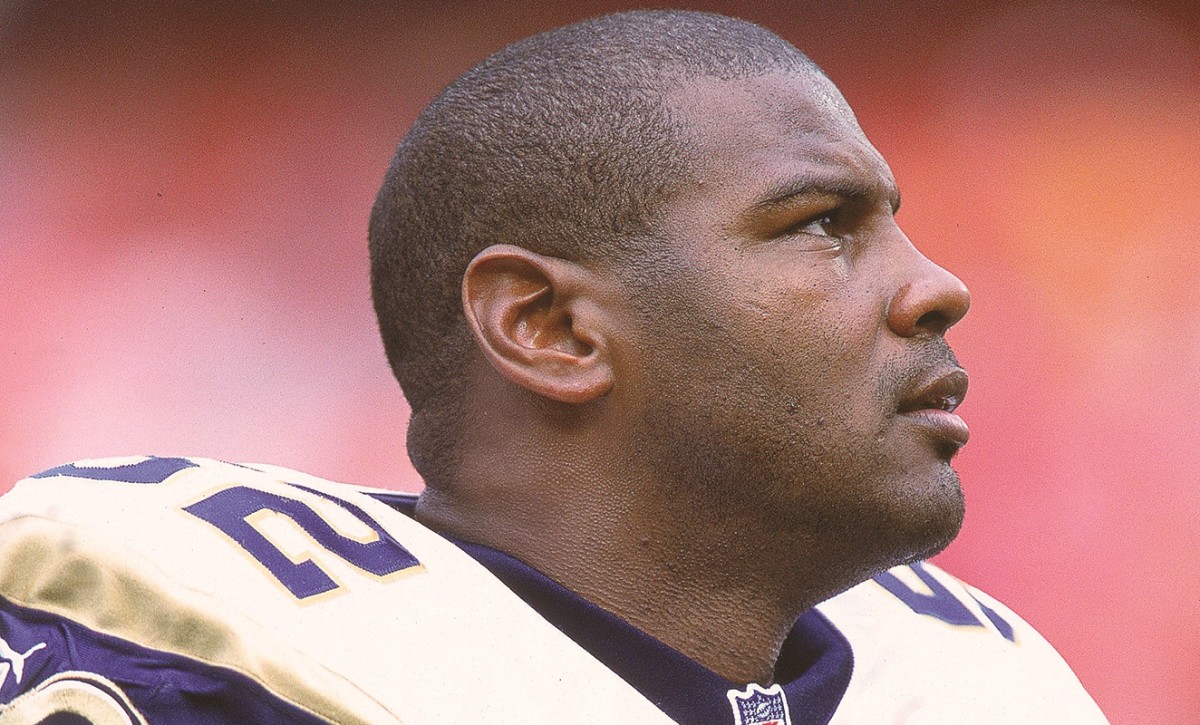

MIKE JONES

What he did: The Tennessee Titans were driving for a potential game-tying score in the final seconds of Super Bowl XXXIV when quarterback Steve McNair hit speedy receiver Kevin Dyson on a crossing pattern at the St. Louis Rams’ 5-yard line.

Dyson had a narrow path to the end zone, but was cut off by Mike Jones, the Rams linebacker who appeared to be covering tight end Frank Wycheck on the play.

Jones quickly pivoted toward Dyson with a lunging grab, wrapping his right arm around Dyson’s right knee and swinging his left arm around like a sledgehammer on Dyson’s left knee.

Dyson fell to the Georgia Dome turf and extended the ball with his right hand toward the goal line, but he was ruled down at the 1-yard line as time expired, with Jones’ tackle securing the Rams’ 23-16 victory on Jan. 30, 2000.

“We were in a matchup zone, like in basketball, and I was the center, so anybody who ran through the middle, I had to be in position to cut them off,” said Jones, now 56. “When the ball is snapped, you see Wycheck go vertical. He’s trying to get me to run off enough that the receiver can run underneath.

“I was covering Wycheck with my body but looking at [Dyson] the whole time. I had to be in position to come back if Kevin came underneath, and that’s what happened. I broke on the ball and caught Kevin in the right spot. If I hit him anywhere but the top of the knee he might have run through the tackle and scored.”

Where he is now: Jones’ 12-year NFL career ended after 2002. He went into coaching, leading Hazelwood East High in St. Louis to a Missouri state title in 2008. He spent one year as Southern University’s linebackers coach, six as Lincoln University’s head coach and five as St. Louis University High’s head coach.

It has been 25 years since his game-saving tackle, but Jones, semiretired with four grandkids and living in Lake of the Ozarks, Mo., still feels the exhilaration of the play.

“Oh man, every time I see that play, it’s like I’m seeing it for the first time,” Jones said. “But if I missed that tackle, you and I wouldn’t be talking right now.”

Nor would he have fulfilled another lifelong goal.

“As a kid, I used to read Athlon Sports and was hoping to have my name in there,” Jones said, “so I finally have a chance to do it.”

DAVID TYREE

What he did: Eli Manning narrowly escaped the grasp of two defenders and was drilled by another as the New York Giants quarterback heaved a pass downfield on a third-and-5 play from his own 44-yard line in the final minutes of Super Bowl XLII against the New England Patriots on Feb. 3, 2008.

Giants receiver David Tyree, a special-teams player who caught only four passes for 35 yards during the 2007 regular season, altered his route as he saw Manning scrambling, coming back toward his quarterback and stopping at the Patriots’ 25.

As the ball arrived, Tyree — with Patriots safety Rodney Harrison draped over his back — made a leaping, two-handed catch above his head.

A swipe by Harrison knocked Tyree’s left hand off the ball, but as the defender pulled the receiver backward toward the ground, Tyree was able to secure possession of the ball by pinning it against the top of his helmet with his right hand.

Tyree fell on top of Harrison, who tried to wrestle the ball away, but officials ruled Tyree had possession, the 32-yard play — forever known as the “Helmet Catch” — giving the Giants a first down at the Patriots’ 24-yard line with 59 seconds left.

Four plays later, Manning threw a 13-yard touchdown to Plaxico Burress with 39 seconds left to give the Giants a 17-14 come-from-behind victory that denied New England’s bid to become the first NFL team to finish a season undefeated since the 1972 Miami Dolphins.

“It was like ‘Chariots of Fire,’ music going on in the background, and you just locked in on that ball,” said Tyree, now 45, during an episode of ‘Giants Chronicles,’ an in-house show produced by the team. “For me, all I remember is going up to high point it …

“I didn’t know anything about the helmet. I just remember getting my second hand back on that ball. All I know is, I got it, and I’m not letting this thing go. It’s a moment in time that is literally, like frozen. I call it a miraculous play that I’m a fortunate recipient of.”

Where he is now: The “Helmet Catch,” which NFL Films’ Steve Sabol called “the greatest play the Super Bowl has ever produced,” was the final reception of Tyree’s career. He missed the 2008 season because of a knee injury, played 10 games on special teams for the Baltimore Ravens in 2009 and retired as a player after that season.

But after serving as the Giants’ director of player development from 2014-19, Tyree parlayed his “Helmet Catch” fame into an entrepreneurial career that included speaking engagements, mentoring, a Madison Square Garden Network show and his own podcast, which ran from 2022-24. Tyree and his wife, Leilah, have seven kids.

“When you’re in the ocean, you sink or swim,” said Tyree, of his career path after leaving the Giants in a 2024 interview for the “Elevate” podcast. “We swam through it. I was able to leverage my own name and get into some media opportunities and do a lot of work.”

TIMMY SMITH

What he did: Timmy Smith figured he’d play some in Super Bowl XXII after rushing for 126 yards in seven games as a Washington Redskins rookie in 1987, but was floored when coach Joe Gibbs told him just minutes before kickoff that he’d be starting in place of hobbled veteran George Rogers.

“Going down the tunnel, my mind went blank,” said Smith, now 61. “I forgot my plays and everything.”

Lucky for Smith, he only had to remember one play, the counter gap, a misdirection run that makes the defense flow one way while the offense — behind one or two pulling linemen — quickly attacks in the opposite direction.

The Redskins ran the play repeatedly in a 42-10 blowout of the Denver Broncos in which Smith rushed 22 times for a Super Bowl-record 204 yards and two touchdowns in San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium.

Washington trailed 10-0 before exploding for a Super Bowl-record 35 points in the second quarter when Smith racked up 122 yards on five carries, including a 58-yard touchdown run. A dominant offensive line, affectionately known as “The Hogs,” anchored by tackle Joe Jacoby and center Russ Grimm, opened huge holes all afternoon.

“They couldn’t stop the counter gap; they couldn’t stop those guys up front,” Smith said. “If they didn’t take me out in the fourth quarter, I might have run for 400 yards.”

Smith rushed for 470 yards and three touchdowns in 14 games in 1988 but was released by Washington after the season.

After failing a physical with the Phoenix Cardinals in 1988, he signed with the San Diego Chargers in the 1989 offseason before suffering an ankle sprain in camp and was released.

Smith signed with the Dallas Cowboys in 1989 but suffered a neck injury in the season-opener and was cut after then-rookie Emmitt Smith ended his holdout. At 26, Timmy Smith’s football career was over.

“That’s why I say NFL — Not For Long,” said Smith, whose Super Bowl rushing record still stands. “After [the Cowboys] released me, I was done with football.”

Where he is now: In 2005, Smith was arrested in a sting operation for selling cocaine to an undercover DEA agent in Denver. He pleaded guilty, claiming he was trying to raise cash for a friend who lost his home, and served 18 months at FCI Englewood, a low-security federal correctional institution in Littleton, Colo.

“I wasn’t a bad guy,” Smith said. “I made a stupid mistake. I did my time, and I learned from it. I’m a new man now.”

Smith lives in Aurora, Colo., and works as a salesman for an energy company. He is married with five adult children and 15 grandkids.

He was recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, which he’s treating with medication and therapy, but his spirits remain high, in part because of his regular speeches to youth groups and spur-of-the-moment conversations with kids.

“You gotta tell them there is no good in hanging around bad stuff, because bad stuff is gonna happen,” Smith said. “Learn to hang out with good people, and they won’t lead you down dumb roads.”

More must-reads:

- Seahawks found a ‘tell’ that doomed Patriots in Super Bowl

- Patriots HC Mike Vrabel discusses Will Campbell's future at LT after disappointing Super Bowl LX performance

- The 'Super Bowl MVPs' quiz

Breaking News

Trending News

Customize Your Newsletter

+

+

Get the latest news and rumors, customized to your favorite sports and teams. Emailed daily. Always free!