Every weekday, Bob Barker would remind viewers to spay and neuter their pets. Of course, he was talking about dogs and cats. Spaying (the surgical removal of the ovaries and uterus in female animals) is a common practice for controlling the population of cats and dogs. However, this is not a premise that is not as prevalent for horses. There are several reasons for this difference in approach.

“The reason that spaying is not that common in horses is that intact horses don't show heat signs similar to dogs and cats,” said Dr. Pouya Dini, an assistant professor at the University of California, Davis, who has studied mare reproduction and behavior. “There are still some behaviors that owners and trainers don't like (with mares in heat), but it's not like dogs or cats. Anyone who has a female cat that is not spayed knows that when they come into heat, they make noise (caterwaul), and they completely change their behavior. When a dog is in heat, she attracts other dogs, and they sniff each other or have blood-tinged vaginal discharges.

“Of course, we see stallion-like behavior in males, and that's why we geld a horse that we don't want for breeding. But in a female, there are not that many undesired behaviors related to their reproductive cycles.”

There are some instances that an owner will complain about a mare’s behavior during her heat cycle. However, Dini stresses to owners that they need to realize that there could be other reasons for the change in attitude or behavior than the normal cycle. One of these reasons could be due to medical issues such as an ovarian tumor which would create a medical reason to remove the ovary.

Dini and his fellow researchers at the Clinical Endocrinology Laboratory at the University of California-Davis have seen a few thousand cases where the owner believes the behavior problem with their mare is related to their ovaries.

“We have hormones that correspond to ovarian ‘health,’ and in 90% of these abnormal behavior cases, there was nothing wrong with the ovary based on these hormones,” said Dini.

If an abnormal behavior is not related to the ovary or the reproductive system, owners really start looking for other reasons: Why is my mare suddenly acting aggressive? Why is she starting to be so bossy? The reasoning behind this change in temperament could be a social issue – what’s been changed around the barn recently? Or, it could be a training issue or even pain in other body parts, such as musculoskeletal issues.

Timelines are flexible with mares

With cats and dogs, there are certain age targets veterinarians prefer for a spay surgery – usually that the animal is mature enough and large enough to safely undergo anesthesia, but still not a fully-grown adult. That’s not the case with horses.

The routine clinical presentation that Dini and his colleagues see is mares that suddenly change their behavior and performance. The mares suddenly start underperforming under saddle or show a decline in their jumping form. Or, in their paddock, they suddenly start bossing around other mares.

“Out of 2,800 cases of abnormal behavior, less than 10% of them were associated with abnormal hormonal levels, indicating an ovarian problem, and the majority of these 10% had one thing in common: they had stallion-like behavior,” said Dini. “These are mares that are teasing other mares -- sniffing them, rearing up, and starting to have a cresty neck. So these are the ones that, okay, there was something wrong with their ovaries.”

In those 10% of cases, the cause of the stallion-like behavior was usually a granulosa cell tumor, or GCT. This is the most common type of tumor found on the reproductive tract of a mare. There is no certain age or breeding that can pinpoint when a mare might develop one – it can happen to a young filly in training or an older retired broodmare.

The Clinical Endocrinology laboratory at UC-Davis has a great diagnostic method for discovering if a mare has a GCT or not. They measure several different hormones, including anti-mullerian, inhibin and testosterone.

“So we measure these three hormones to see if there is potentially a tumor in the ovary or not. We also ultrasound and feel their ovaries to evaluate how they look and measure their size” said Dini. “But the majority of cases do not have a tumor. Maybe there is a new mare in that paddock; that's why our mares start changing their behavior. Maybe it's a new trainer, or maybe something changed in the lifestyle of the mare. But owners tend to ignore those and go directly to the medical route.”

Side effects of spay

Mares’ ovaries produce two main steroid hormones: estrogen and progesterone. When a mare is in heat, there is estrogen but no progesterone. That is why she shows signs of heat, such as teasing into a stallion, squatting, and urinating for a few days. Once out of heat, ovaries produce progesterone, which suppresses the teasing behavior. The squatting and urinating are all suppressed. Once you remove the ovary, you're removing that source of progesterone, while the adrenal glands can produce some estrogens, and there will be no progesterone to block its effect and the balance is out of whack. This now leaves you with what is called a “teasing mare.”

“We need to make sure that the ovary is the problem before we remove them otherwise you'll make a new problem by removing the ovary because you're removing that source of progesterone,” said Dini.

Specialists like Dr. Dini work with owners to scrutinize every facet of the mare, from her daily routine and habits to her eating in regard to her cycle. If the hormonal test comes back normal, they will still palpate the ovary to make sure that, anatomically, the ovary looks normal.

The next step will be to have the owner mark on a calendar whenever the horse behaves abnormally, and make notes as to what they feel could be the cause. In th spring and summer, mares cycle every 20-21 days, so if the issue is due to the ovary, the change can start to happen when a follicle starts to grow on the ovary, becoming too big and causing the mare to be uncomfortable. Again, this cause has been rare, but Dini has seen it happen and he won’t completely rule it out without testing.

“If you see a pattern on the calendar, then it probably can be the ovary,” he said. “That’s when we start to monitor them more closely to see when she becomes colicky or starts to act aggressive.”

There are medications that can induce ovulation to get rid of a big follicle, which gets rid of the pain. This should clear the behavior as well.

“If the behavior goes away, then we know that's an issue with the ovary,” said Dini. “That means that the ovary is a candidate to be removed; even though it’s not a tumor, there is some other issue there.”

If surgery is needed

In days past, to spay a mare you needed to put her under full anesthesia, place her on the operating table, and open up her belly. Now, surgeons are able to keep the mare standing while under anesthesia and go in from the side (paralumbar) to remove the ovary. It's a small incision, so there isn’t a big scar. While this is a big advantage, you have to remember that you are still going inside the abdominal cavity of the mare. This is not a procedure that can be performed on the farm, like castrating a colt.

“However, the procedure is very fast and also safe, at this point, for most of the horses,” said Dini. “We’ve been able to do this for several years now.”

Unlike a gelding procedure where it’s safe to ride the horse almost immediately after, a mare will need at least a week or two to recover from the surgery. Mares typically need at least a few days of stall rest and then a week of very low exercise and then they can typically go back to their normal routine.

Meanwhile, in Europe

European horse owners are tackling certain behavioral issues of mares not with spay surgery but with vaccines. There is a similar vaccine that was once used to reduce boar taint in for pigs, according to Dini. This vaccine works against Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). This hormone is made by the hypothalamus to eventually induce the ovary or testicle to produce steroids.

Currently, this vaccine is not available in the United States, but it has been used in Australia and Europe. The vaccine will shut down ovarian hormone production from six months to a few years. A booster is sometimes required to keep the shutdown going. There are studies showing that this vaccine improves abnormal behavior in some mares.

In the United States, without this option, some people may learn towards surgical removal of the ovaries. Dini advises caution with this approach.

“Some owners might like the change they see in their mare after the ovaries are removed, but at what cost?” he says. “We are spending a few thousand dollars and we will be satisfied because of the money that we spend. But does it really help the mare? Without really testing and looking into the problem, that's questionable. Those ovaries could have been normal.”

More must-reads:

- DeMeco Ryans sounds displeased with officiating after C.J. Stroud concussion

- Mike Vrabel responds to accusation that Patriots simulated Falcons' snap on key fourth-quarter play

- The 'NFL Passing YPG leaders' quiz

Breaking News

Trending News

Customize Your Newsletter

+

+

Get the latest news and rumors, customized to your favorite sports and teams. Emailed daily. Always free!

TODAY'S BEST

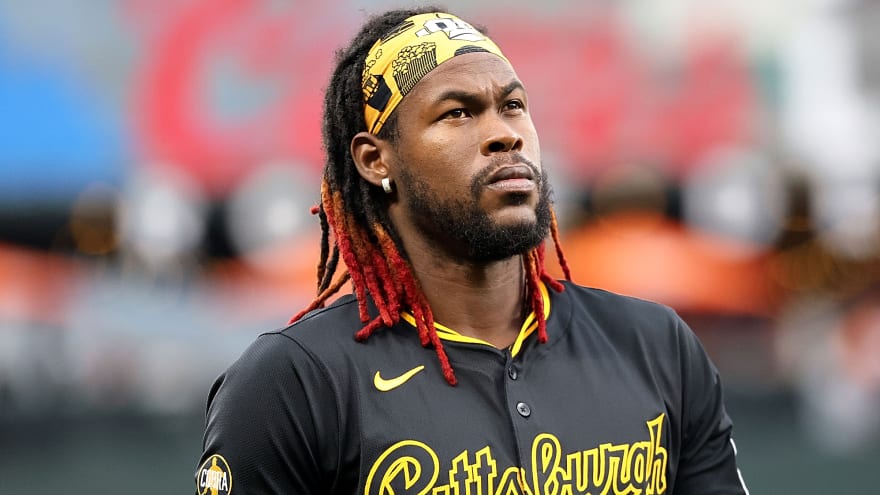

Steelers Are In Position To Make Interesting Trade For 2023 First Rounder To Strengthen Defense

The Pittsburgh Steelers pulled off an upset victory at home on Sunday over the Indianapolis Colts. The Colts came into the Steel City riding high, boasting one of the most complete offenses and teams in the NFL. The Steelers were three-point home underdogs, but the game quickly started going Pittsburgh’s way. The defense forced six takeaways from the Colts’ offense, and the Steelers held on to win 27-20, sending a statement across the league. Now, with the trade deadline hitting on November 4th, all eyes are on contenders to see what moves they might make at the last minute as they try to improve their rosters for the crucial stretch of the 2025 season. Steelers General Manager Omar Khan has made it clear through his history of bold moves that he will always bang the phones if he sees a chance to strengthen the roster. With the Steelers in such a unique spot this season with Aaron Rodgers only in town for 2025, timing is critical. The focus has largely been on acquiring another weapon for Rodgers, but on Monday, Steelers insider Brian Batko revealed another potential target. He mentioned former 2023 first-round pick and New York Giants cornerback Deonte Banks as a possible trade option in his article for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. With the Steelers showing defensive dominance on Sunday and the trade deadline approaching, fans and pundits alike are watching closely to see if Khan can pull off another impactful move before the critical stretch of the season. "One of the more intriguing ideas is to offer a change of scenery for Giants cornerback Deonte Banks, a 2023 first-round pick who visited the Steelers before that draft and has been benched at times this year for a 2-7 team," Batko said on Monday. Like Batko mentioned, Banks was a player the Steelers had interest in back during the 2023 NFL Draft when he was coming out of Maryland. Banks is now in a unique situation with the Giants, where he has lost his footing on the depth chart and the team is not competitive. That means they could be sellers, and Banks could become an option for Pittsburgh. Another intriguing idea from Batko is Seattle Seahawks cornerback Riq Woolen, but because the Seahawks are now contenders, acquiring him could be trickier. "Riq Woolen, the speedy 6-4 cornerback who has reportedly fallen out of favor in Seattle, would be fun but might be needed for a Seahawks team that’s put itself in contender territory," Batko said. There are all sorts of directions that Khan and the Steelers front office can go. With the Steelers sitting at 5-3 and in first place in the AFC North, the time is now to leave no stone unturned and figure out how to maximize the 2025 season with Rodgers. Khan could try and add a wide receiver to this roster but it also sounds like a defensive trade is also on the table. Steelers Are In A Rare Spot The Steelers are in a rare position this season where a smart move could have an immediate impact. With a veteran quarterback like Rodgers leading the offense, even one addition on either side of the ball could shift momentum in the critical final stretch. The front office has shown a willingness to be aggressive in the past, and with the trade deadline looming, they have a window to make a statement. Fans and analysts will be watching closely to see if Khan can identify the right pieces without sacrificing future flexibility. Whether it’s shoring up the secondary with a cornerback like Banks or adding another weapon for Rodgers, the next few days could define how competitive Pittsburgh is in the AFC this year. What trades do you want to see the Pittsburgh Steelers make before the trade deadline hits on November 4th?

DeMeco Ryans sounds displeased with officiating after C.J. Stroud concussion

Quarterback C.J. Stroud suffered a concussion in the second quarter of the Houston Texans' 18-15 home loss to the Denver Broncos on Sunday when he took a crunching hit as he attempted to slide following a scramble. Broncos cornerback Kris Abrams-Draine was initially penalized for unnecessary roughness, but referees eventually picked the flag up after a replay showed that Abrams-Draine hadn't hit Stroud in the head. While speaking with reporters on Monday, Texans head coach DeMeco Ryans addressed his thoughts on that play. C.J. Stroud concussion showed when quarterbacks are, aren't protected "It’s a tough play," Ryans said, per Jonathan M. Alexander of the Houston Chronicle. "Quarterback is sliding. I thought quarterbacks are protected when they slide. But what I’m learning is, as long as you don’t hit them in the head or neck area, if they slide and you hit them in the chest, then that is just fine. That is what I learned." As ESPN's DJ Bien-Aime shared, Ryans said shortly after the Texans fell to 3-5 on Sunday that he felt the hit on Stroud was unnecessary roughness because Abrams-Draine "hit the quarterback when he was sliding and giving himself up." Stroud was still in the NFL's concussion protocol as of Monday afternoon, and it's unclear if he'll be available for Houston's home game versus the Jacksonville Jaguars (5-3) on Nov. 9. "I spoke to him last night," Ryans said about Stroud. "He’s feeling a little bit better. We’ll see how the week goes and how he progresses throughout the week." What Texans would expect if Davis Mills has to start vs. Jaguars Backup quarterback Davis Mills replaced Stroud against the Broncos and completed 17-of-30 pass attempts for 137 yards with no touchdowns or interceptions. Mills began Monday atop the Houston depth chart with Stroud not cleared to practice. "I expect him to go out and do his best," Ryans said about Mills possibly getting the start for the Jacksonville game. "Just play the offense the proper way and make great decisions with the football." Shortly after Ryans spoke with media members, ESPN BET had the Texans as 1.5-point favorites over the Jaguars. Ryans may not reveal Stroud's status for the Jacksonville game before Friday at the earliest.

The 'NBA 20-season club' quiz

Kyle Lowry checked in for the end of the Philadelphia 76ers 129-105 victory over the Brooklyn Nets and he joined an elite group once he stepped on the hardwood. The Villanova product and former 24th-overall pick in the 2006 NBA draft became the 12th player in NBA history to play in 20 NBA seasons. It was Lowry’s first game action of the season for the 5-1 Sixers, and the Philadelphia-native made his lone field goal attempt in garbage time. “Who would have thought it for Kyle Lowry 20 years ago, right?” said head coach Nick Nurse after the win. While Lowry doesn’t have much of a role on the floor for Philadelphia at this stage of his career, Nurse said he’s still a valuable asset to the team. “He’s done a great job being part of our leadership group,” Nurse said of Lowry. “When the players are pulling for him out there, you can tell he’s well-liked and well-respected.” Which brings us to today’s quiz. How many of the 12 NBA players to play in at least 20 seasons can you name in five minutes? Good luck! Did you like this quiz? Are there any quizzes you’d like to see us make in the future? Let us know your thoughts at quizzes@yardbarker.com, and make sure to subscribe to our Quiz of the Day Newsletter for daily quizzes sent right to your email!

Mike Vrabel responds to accusation that Patriots simulated Falcons' snap on key fourth-quarter play

With under two minutes remaining in regulation of Sunday's game between the Atlanta Falcons and the New England Patriots, Atlanta quarterback Michael Penix Jr. committed a costly and curious intentional grounding penalty after he seemed not ready to receive the snap of the football. Following the 24-23 loss that dropped Atlanta to 3-5 on the season, Falcons head coach Raheem Morris accused Patriots players of "clapping" to simulate Penix asking for the ball to be snapped. During a Monday appearance on Boston sports radio station WEEI, first-year New England head coach Mike Vrabel responded to Morris' comments. Mike Vrabel "didn't see" Patriots players simulating the snap "I mean, I didn't see anything," Vrabel said, per Tom Carroll of Audacy. "Like, is that fake? I don’t know. Quarterbacks, when they want the ball, it’s like [clap] [clap] [clap] [clap]. I mean, I didn’t see anybody doing that. And then, like, we don’t do the clap…I can see, like, when the quarterback, like it’s the silent count, it’s like [softer claps], but I didn’t see anybody do that." The CBS broadcast of Sunday's contest didn't show a single New England player clapping before the ball was snapped for what became the intentional grounding play. As Marc Raimondi of ESPN noted, a team guilty of simulating an offense's snap count or snap is supposed to receive a 15-yard penalty. No flag was thrown before the ball left Penix's hand, and the Falcons eventually had to punt on fourth down of that late drive. From there, New England was able to run the clock out. Mike Vrabel names latest Patriots-related controversy The Patriots were previously part of "Spygate" and "Deflategate" scandals. On Monday, Vrabel named the latest alleged New England controversy. "'Clapgate,'" Vrabel added during the segment. "That was new. I didn't see that. I just know - and maybe that's a testament to our fans. You know what I mean? It got loud, and I could hear the energy, and so thank them for that. But that's a good point. I did not - I didn't see anything, and I’ll let you guys go investigate." The 7-2 Patriots next play at the Tampa Bay Buccaneers (6-2) on Nov. 9. Perhaps it's fair to wonder what New England players will and/or won't try to get away with at Raymond James Stadium during that Sunday afternoon matchup.