Ghost hunter: How Shoeless Joe Jackson became bartender's obsession

Dan Wallach never dreamed years ago of someday chasing the ghost of Shoeless Joe Jackson.

Of traveling to Americus, Georgia, to collect treasures from a ballfield where Jackson might have run. Of driving to Bastrop, Louisiana, to stand where the former big-league star once roamed the outfield. Of giving up his job as a bartender near Wrigley Field and moving from Illinois to Greenville, South Carolina — Jackson's hometown — to become executive director of the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum.

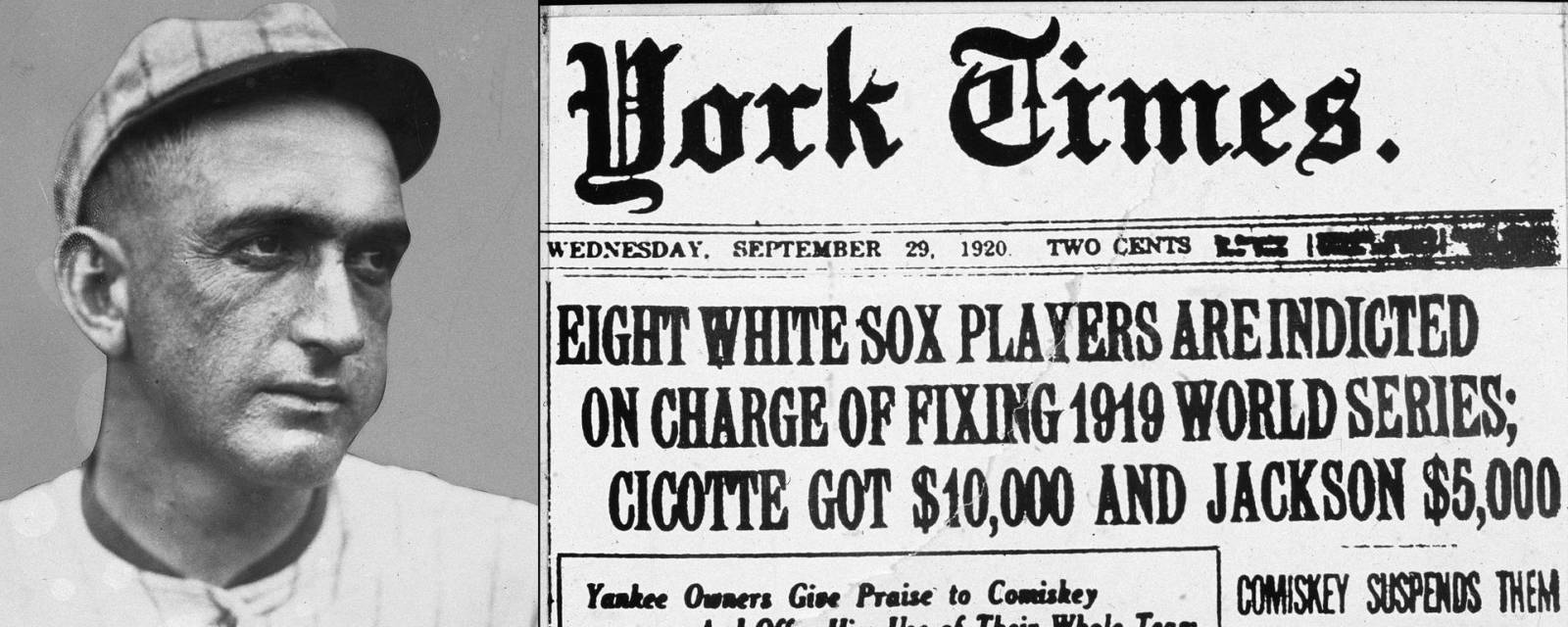

One hundred years ago, Jackson's name was dragged through the mud during the infamous Black Sox World Series scandal. Now Wallach, a 32-year-old baseball historian/museum director, digs deep to uncover everything about Shoeless Joe.

This is a story of his obsession. And of dirt.

Lots of dirt.

Throughout his childhood and young adulthood, Dan Wallach was drawn to the story of Joseph Jefferson Jackson — what his father, Mike, calls “the romanticism of Shoeless Joe.” He knew the general outline of Jackson's 13-year Major League Baseball career: .356 lifetime average playing for the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Naps and Chicago White Sox; .382 batting average in his final campaign in 1920; banned from baseball for his still-disputed role in the 1919 Black Sox gambling scandal and thus ineligible for the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Wallach enjoyed popular movies “Field of Dreams” and “Eight Men Out,” which featured Shoeless Joe storylines. Dan and Mike, an ardent baseball historian and collector, are longtime fans of the White Sox, for whom Jackson starred from 1915-20. But his passion for the Sox was just one of many, along with all things Michael Jordan and a treasured collection devoted to Alkaline Trio, a legendary Chicago punk band.

In 2008, Dan traveled to Greenville for a visit with his recently retired parents. By Day 2, the 22-year-old was bored. He looked up local attractions and discovered the Shoeless Joe Museum was nearby.

Two years earlier, the house in which Jackson died in 1951 was moved from its original location to near Fluor Field, where Shoeless Joe once played ball. The small brick house was restored in 2008, opening as a museum at 356 Field Street, a nod to Jackson's lifetime batting average.

When Dan walked into the museum, a woman asked what position he played.

“Uh, second base?” he said. “I played some shortstop in high school.”

“Good,” Wallach recalls then-museum president Arlene Marcley telling him. “Our first vintage baseball game is Saturday. You’re second base.”

“Why not?” he said with a shrug.

Seven years later, in 2015, Wallach became truly hooked on Jackson's story.

“I became more and more involved with the museum and built relationships with all the people who play in the [vintage baseball] event, and it increased my willingness to do this crazy research,” he says. “Just by nature, I’ve always been the type of guy who researches online. I’m a collector and researcher by nature. To me it was a no-brainer to learn about Joe, and to learn as much as I possibly could.”

In pursuit of that goal, he travels the country, collecting Shoeless Joe mementos from every stop. He gets most excited about the mundane items — a brick from a building that may have housed Jackson's laundromat or a key from the hotel in Cincinnati where White Sox players stayed in 1919 and reportedly met with gamblers to throw the World Series. Relatively few authentic relics from Jackson's big-league career are known to exist. One of them, Jackson's "Black Betsy" bat, sold at auction for $583,500 in 2016. Wallach could never afford such high-priced items himself, and besides, he says, “You can’t even touch objects like that.”

What makes Jackson's life most interesting, Wallach says, is his life away from baseball.

“A lot of players in the Hall of Fame, their story begins and ends with their career," he says. "Joe lived a successful life after baseball, and I guess maybe it’s because he was forced to.”

Not much is officially known about Shoeless Joe’s life after his professional baseball career. Museum board members Mike Nola and Jacob Pomrenke have created post-MLB timelines for Jackson, but Wallach aims to fill in gaps in Shoeless Joe's life story.

“That’s something I like to do with road trips,” he says. “For me, it’s not just about the baseball fields he played on but the businesses he owned, the houses he lived in. I’m trying to go everywhere.”

Wallach hopes to educate people that Jackson’s banishment from baseball was not a death sentence. “A lot of people look at Shoeless Joe’s life and call it a tragedy,” he says. “To look at him as a tragic figure would be to assume his entire identity was his baseball career."

Despite barely being able to read and write, Jackson was a successful businessman, Wallach says. He owned a laundry in Savannah, Georgia, pool halls in Chicago and New Orleans, and a barbecue restaurant and liquor store in Greenville.

“Now,” Wallach adds, “was his baseball career a tragedy? Well, he had the respect of all of his peers — Babe Ruth said he copied his swing and Ty Cobb called him the best pure hitter he’d ever seen — and he had a World Series ring and a bunch of records. Tragedy is an interesting concept, and I can understand why people can see parts of his story being tragic."

Shoeless Joe had already made a name for himself in Louisiana by the early-1910s when he starred for the minor league New Orleans Pelicans. But in 1923, three years after his banishment from Major League Baseball, Jackson found himself back in the bayou, in Bastrop, population about 1,200. He played nearly two dozen games before word got out that anyone who played with or against Jackson would have their names tarnished.

Wallach researched from afar that time in Jackson’s life with little success, so he drove 760 miles from Illinois to Bastrop, arriving on a weekend when nearly everything was closed. “I couldn’t do the research like I normally would — go through microfilm, search through newspaper clippings -– so I had to get creative,” says Wallach, who was eager to find where Jackson played ball in the Louisiana town.

Dan sought answers in, of all places, a Home Depot. "Do you remember an old baseball field around here?" he asked customers and anyone else who would listen. He got a lead but no definitive answer. “Six different stories from five different people.”

MORE: Story of Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum in Greenville, South Carolina

On a hunch, Wallach stopped at a local retirement home, where he met the wife of the former Bastrop mayor. She confirmed one of Wallach's Home Depot tips about the Jackson ballfield. Minutes later, he stood in what used to be the outfield. For a moment, Wallach was in 1923, right by Joe’s side.

“It’s cool to put myself in his shoes — no pun intended,” says Wallach. “Like … Joe was here. He stood in this box. He played on this field. As cool as that feels, part of what makes it fun to me is the hunt. Having to hunt down the wife of a former mayor in a town that Joe played in for three weeks. A lot of people hear me tell these stories and they say, ‘Why do you care? It doesn’t mean anything.’

“Well, it does for me.”

Wallach, who was named executive director of the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum in May, has bold plans and big ideas for the attraction. The museum is in the process of being moved not far from its current location. Dan and the museum board aim for it to be open seven days a week.

Mike Nola, one of the foremost Shoeless Joe experts, understands Wallach's passion because he shares it.

“Dan’s chasing that dream: to hold something Joe held or see something Joe saw,” he says. “I get that because I’m the same way. I got a letter from his sister once. A letter about someone from Chicago wanting to hire him to give a batting demonstration. She saw I was fascinated by the letter, tore it out of the scrapbook and gave it to me. A few years ago, I noticed some pencil writing on the back, held it up to the light. What do you think I found? A Shoeless Joe autograph, just glued in there. I was amazed. So I get Dan’s motivation and his passion.”

Not everyone does. When Dan began collecting dirt from ballfields associated with Shoeless Joe, few understood why.

“I don’t even think my dad got it,” he says. “I said, 'I’m driving from Chicago to New Orleans to get a jar of dirt.' I mean, it sounds stupid. I’m not trying to convince anyone it’s not stupid. But it’s my stupid.”

Dan's wrong about Dad. Mike Wallach is elated about his son's pursuit of all things Shoeless Joe.

“I will never step on someone’s passion,” says Mike, who serves as managing director of the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum. "I’ve never said to Dan, 'That’s enough.' The biggest risk in life is not taking one. I want him to do it. To leave Chicago, to come to this small, little town and to take this museum to new heights.

“I hope this is exactly what he wants in life.”

This is what he wants in life.

Dan is about to turn 33, Shoeless Joe's age when he was banned from baseball, a fact that he says helped motivate him to make the move to South Carolina. “I’m leaving my friends, I’m leaving my home, my job,” Dan Wallach says, “and I’m doing it. I’m doing it for Joe.”

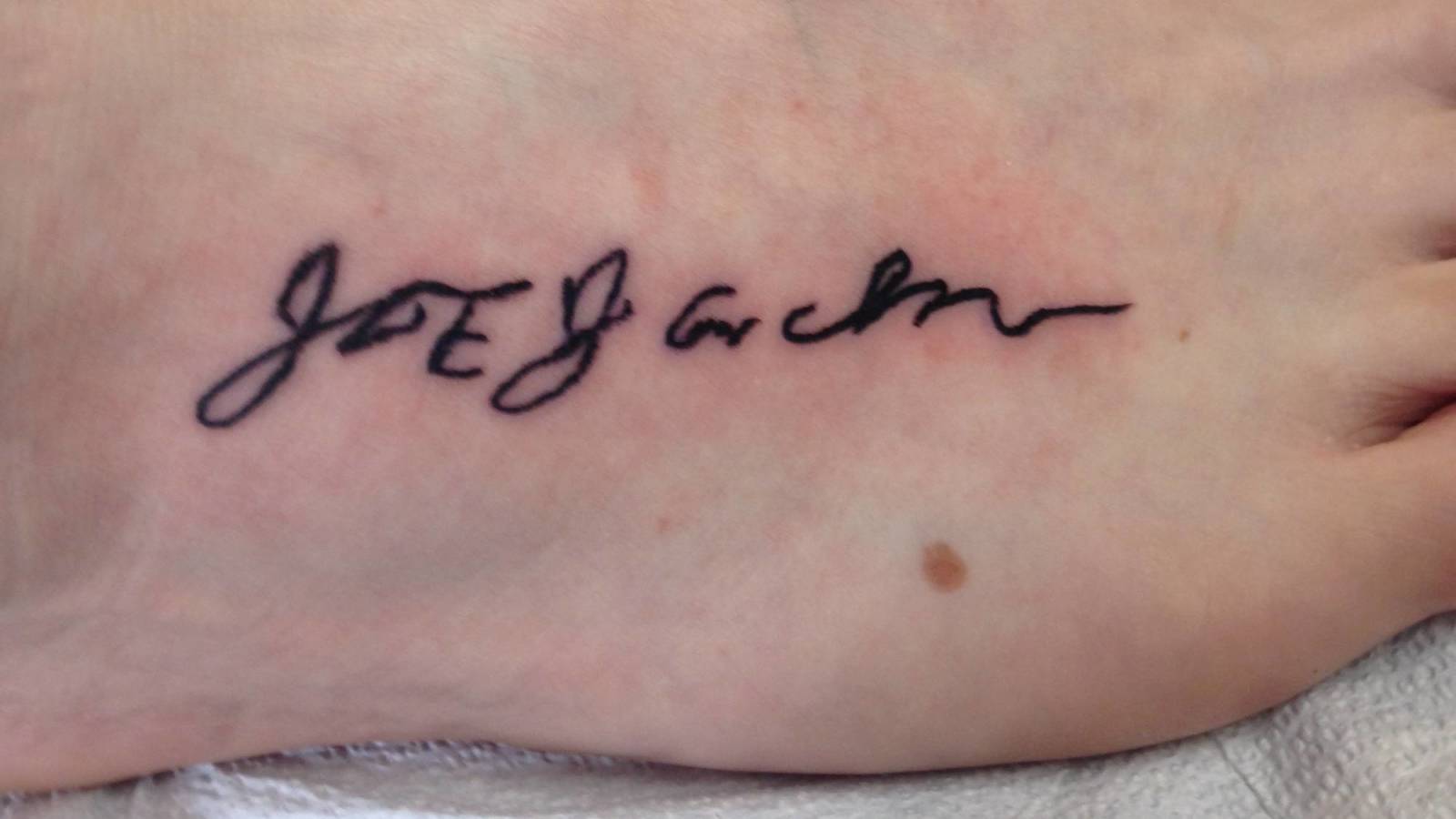

And he has the ink to prove it.

On his right foot, Dan has a tattoo of Joe Jackson’s signature.

It is one of his prized possessions, and he loves it, mainly because you can only see it when he’s shoeless.

More must-reads:

- Mariners getting needed bat in All-Star Brendon Donovan via three-team deal with Cardinals, Rays

- Giants CEO calls Dodgers a 'dragon to slay'

- The 'MLB active doubles leaders' quiz

Breaking News

Trending News

Customize Your Newsletter

+

+

Get the latest news and rumors, customized to your favorite sports and teams. Emailed daily. Always free!