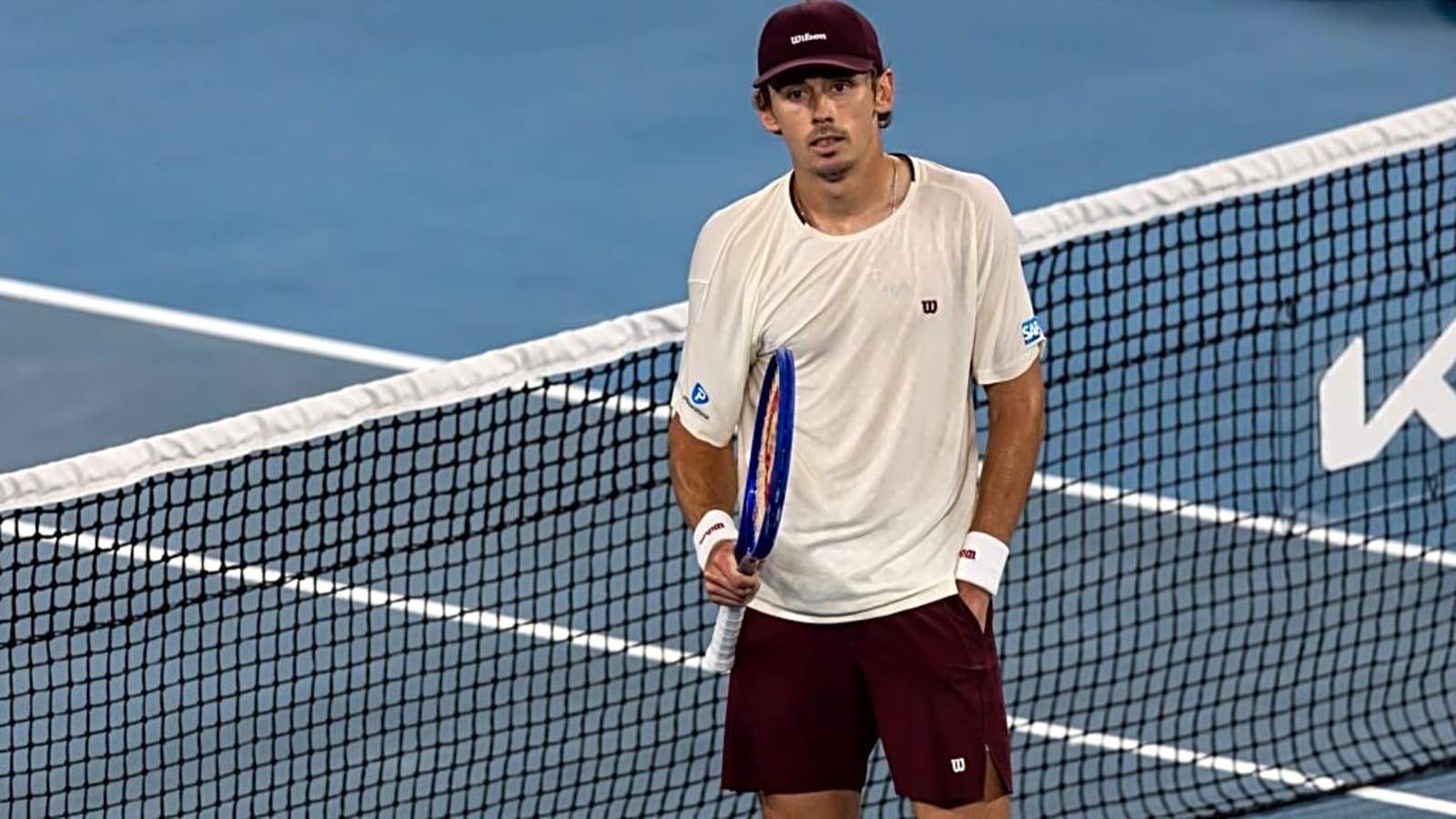

Alex de Minaur has been good for a very long time. Good enough to matter, enough to make draws more difficult and collect wins against players who should beat him. But good doesn’t become great simply by waiting.

For years now, de Minaur has occupied that uncomfortable territory just below tennis’s summit. He’s been ranked high enough to merit attention, consistent enough to make quarterfinals feel routine. Yet when analysts list the sport’s elite, his name comes late in the conversation, if at all.

The truly elite tier in tennis holds maybe two players, perhaps three on generous days. de Minaur has never belonged to that group. Everyone understood this, including him.

But something may be changing.

de Minaur’s Patient Climb

Six years ago, de Minaur cracked the Top 20. It happened in 2019, which feels like a different tennis era because it was. That breakthrough seemed to promise rapid ascent.

The rapid ascent never came.

What followed instead was something different: grinding improvement. This is the kind of improvement that shows up in year-end rankings rather than highlight reels. While contemporaries like Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner launched themselves into the sport’s stratosphere, de Minaur climbed one rung at a time.

Number 15 in 2021. Number 11 in 2023. Top 10 in 2024, eventually reaching number six.

The progression tells a story about a player who improved every year but never dramatically enough to change the narrative around him. His game mirrors this trajectory: relentless, efficient, maddeningly consistent, rarely spectacular. He won by degrees, not explosions. The tennis world moved past him simply because others evolved faster. de Minaur simply kept working, kept climbing, earning wins against everyone except the absolute best.

Now he stands on the precipice of something different. The 2026 Australian Open has delivered the highest level of tennis he’s ever produced. Melbourne’s center court awaits. So does Carlos Alcaraz.

The Numbers Tell Their Story

Consider de Minaur’s serve, historically the weakest element in his arsenal. Last year at the Australian Open, he hit his first serve 51 percent of the time and won 76 percent of those first-serve points. Respectable numbers.

This year, he’s hitting first serves 61 percent of the time.

Ten percentage points separates solid from dangerous. The sample size remains small. But the eye test confirms what the numbers suggest. He’s winning 77 percent of first-serve points, roughly the same conversion rate as last year, but the increased volume transforms the equation. More first serves mean more free points, more pressure, and more opportunities to dictate rather than defend.

Every other metric has shifted similarly. Some marginally, some significantly, but all pointing in the same direction.

The forehand particularly demands attention. de Minaur built his reputation on speed and defense, on retrieving impossible balls and extending rallies until opponents cracked. The forehand existed mostly to facilitate that strategy.

Watch him now, and the weapon has transformed. He’s attacking with it, finishing points with it, and hitting through opponents rather than around them. The confidence radiates through every swing. This isn’t the same player who entered 2025.

Whether this constitutes a genuine leap or simply his best week remains unknown. Tennis has a way of humbling players who mistake a hot streak for transformation. But something feels different this time.

Alcaraz will answer the question.

The Ultimate Test

Carlos Alcaraz represents everything de Minaur is not: explosive, overwhelming, capable of shotmaking that defies physics. When Alcaraz plays his best tennis, the outcome becomes inevitable. The only question is whether the match will be competitive.

de Minaur has never possessed the weapons to match that level. His game revolves around consistency, around making opponents beat him rather than self-destructing. Against Alcaraz, that approach typically leads to respectable losses.

The pressure Alcaraz generates separates the very good from the elite. He doesn’t simply hit winners; he creates situations where winners become necessary, where anything less invites destruction. Unless you can match him shot for shot, you find yourself defending until defending becomes impossible.

de Minaur hasn’t demonstrated that capacity yet. His game remains built on different principles.

But perhaps this moment changes the equation. If ever there was a legitimate chance of an upset, Melbourne provides the stage. Alcaraz has struggled here historically, never quite solving the Australian Open’s particular challenges. Home soil matters. The level de Minaur has shown this fortnight matters. This isn’t the player who lost meekly in previous meetings. This is someone who might finally possess the weapons to make Alcaraz uncomfortable.

What’s Next?

Whether de Minaur wins or loses against Alcaraz may matter less than the level he brings to the match. Beating the world’s best once could represent variance. Competing with them genuinely suggests something more permanent.

The six-year climb from Top 20 to Top 10 demonstrated character and work ethic. The climb from Top 10 to elite requires something else: the ability to hurt players who previously hurt you.

de Minaur may be discovering that ability now, at 26, after years of patient development. Or this could simply be his best two weeks before regression to his established level.

Time will tell. Alcaraz will tell.

For now, Australian tennis has its moment. de Minaur has spent years climbing toward this opportunity. The question is whether he’s finally ready to seize it.

More must-reads:

- Mets' Carlos Mendoza again addresses Juan Soto, Francisco Lindor relationship

- Former GM sounds alarms about Jets HC Aaron Glenn after disastrous first season

- The 'MLB active doubles leaders' quiz

Breaking News

Trending News

Customize Your Newsletter

+

+

Get the latest news and rumors, customized to your favorite sports and teams. Emailed daily. Always free!