Recently, there’s been a lot of discussion in the media about “Ring Culture.” So, what is it exactly? To most, “Ring Culture” has become synonymous with valuing winning championships and obtaining championship rings as the ultimate measure of a player’s or team’s success. As a result, this culture has led players and fans to prioritize championship wins over other accolades or individual achievements.

LeBron James recently weighed in on the Ring Culture phenomenon during an episode of his Mind the Game podcast with co-host Steve Nash.

When asked where Ring Culture came from and where it started, James replied, “I do not know the answer.“ He added, “I wish I had the answer to this, but I’m not sure. Man, it’s funny. Yeah, I don’t know. I don’t know why it’s discussed so much in our sport and why it’s the end-all, be-all of everything.”

James’ highly scrutinized comments mirrored a growing sentiment that measuring a player’s worth by rings alone may be unfair, especially when the likes of Charles Barkley, Patrick Ewing, Reggie Miller, and his co-host Nash, to name a few.

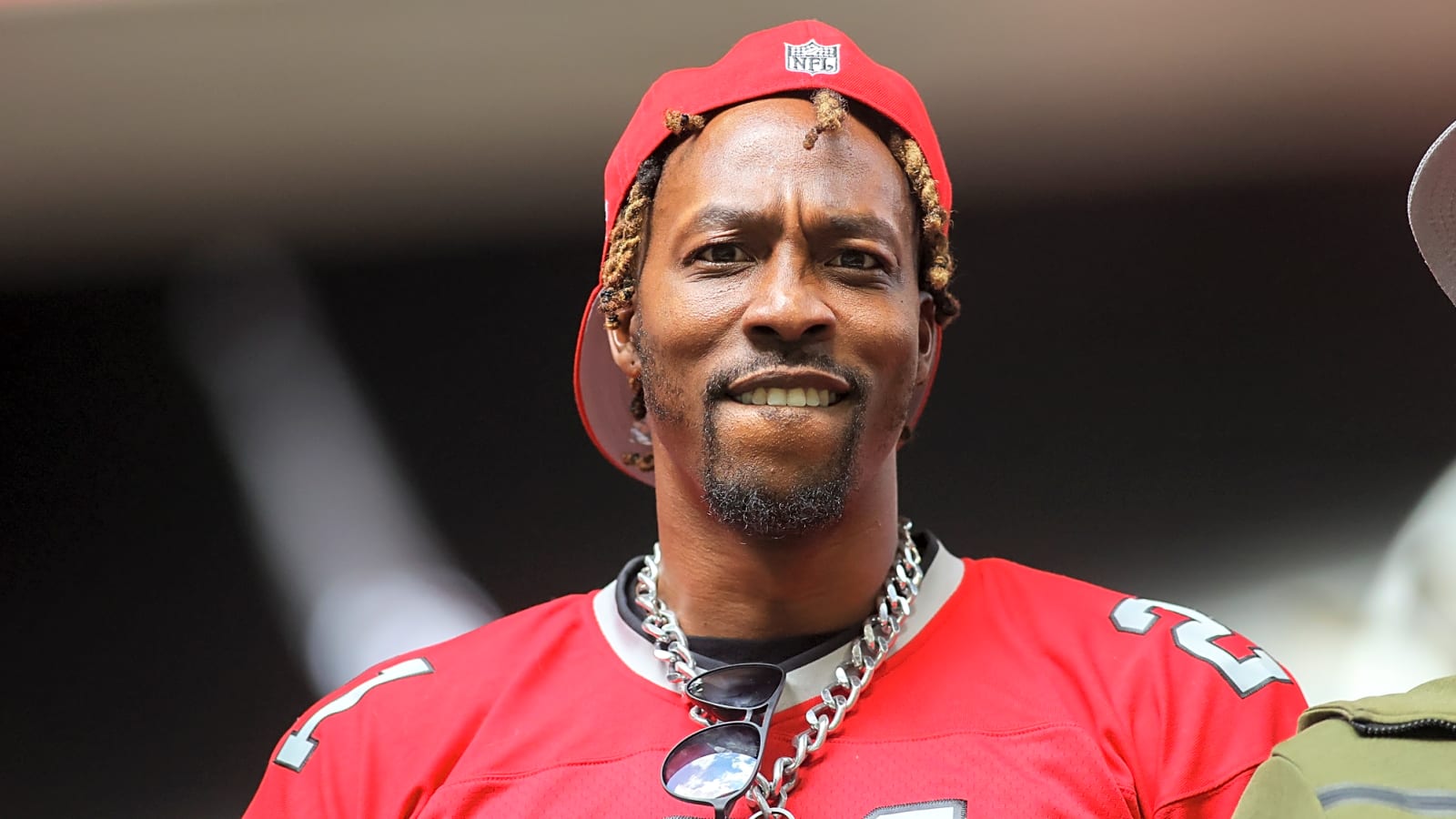

On the PBD Podcast, LeBron’s former teammate Dwight Howard echoed this opinion whilst offering push back to host Patrick Bet‑David’s incessant and exhausting chatter about Bron’s rings.

“I think that we have had so many great players and greatness come through this league, we start to compare by using rings. I think it takes away from a lot of the greatness that a lot of these players had because they weren’t as fortunate enough to win championships like Jordan or, you know, LeBron did.”

Howard’s words struck a particular chord: deeming rings the measuring stick diminishes the legacy of many legends whose stars shone brightly regardless of championships. Howard himself was a victim of this yardstick until he won a ring in 2020. Despite that ring, he still finds himself as the butt of Shaquille O’Neal’s jokes, because the big man claims he only has one ring to Shaq’s 4.

He continued with another razor-sharp observation on how branding can shadow true greatness. “[Some players didn’t] have a brand push them to a whole another level. Larry Bird, or let’s say, Clyde Drexler, or even Scottie Pippen,” he said.

“These guys have the engine of Nike behind them, or you know, how Steph Curry has Under Armour and stuff like that. So when you don’t have that boost behind, you may not get the credit from the world because the eyes are not on you as much as it would be if you were with these companies.”

Howard highlighted an often-overlooked truth: endorsement power can magnify—or mask—a player’s impact.

Take Scottie Pippen. He signed with Nike in 1991—by then, he had already earned his first NBA title alongside the great Michael Jordan—and later launched the Nike Air Pippen 1 signature shoe near the end of the 1996‑97 season. Even then, he frequently stood in Jordan’s shadow.

Clyde Drexler did not catch a break from any major brand. He instead cycled through smaller companies, such as KangaROOS, Avia, Reebok, and Avant Guard—brands that lacked the marketing muscle of Nike or Under Armour. That likely limited how the public perceived his Hall of Fame career.

Howard’s twin critiques on the PBD Podcast attempt to reset the conversation. First, ring counts alone do not define greatness. Second, a lack of branding investment can undermine a legend’s cultural footprint, even if the talent is undeniable.

More must-reads:

- What this slumping Thunder standout must do in Game 7

- Kevin Durant, DeMarcus Cousins get into feud over 'fistfights' claim

- The 'Most points with zero assists in the NBA Finals' quiz

Breaking News

Trending News

Customize Your Newsletter

+

+

Get the latest news and rumors, customized to your favorite sports and teams. Emailed daily. Always free!